The Sardex factor (Financial Time Copyrights)

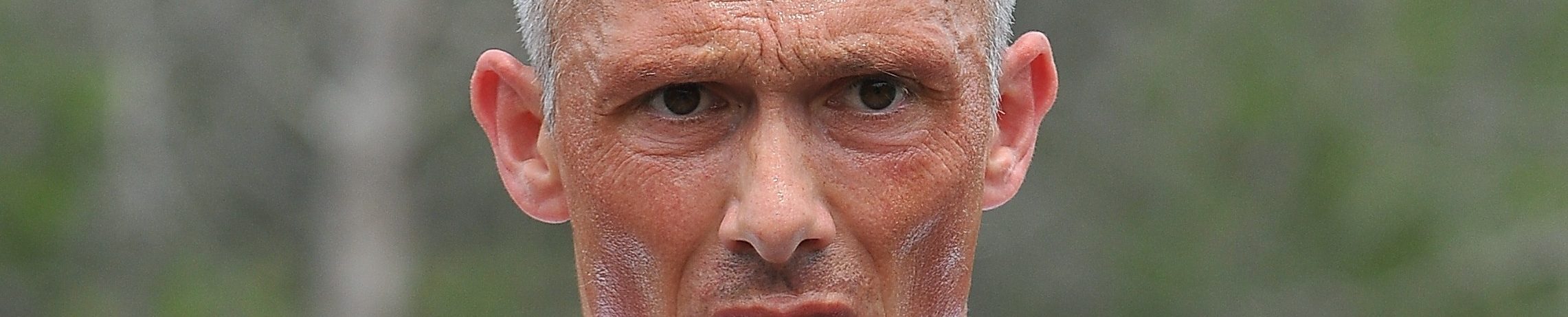

The Sardex factor When the financial crisis hit Sardinia, a group of local friends decided that the best way to help the island was to set up a currency from scratch Sardex’s founders outside their office in Serramanna, Sardinia Share on Twitter (opens new window) Share on Facebook (opens new window) Share on LinkedIn (opens new window) Save Edward Posnett SEPTEMBER 18 2015 30 Print this page Across the island of Sardinia there are more than 7,000 ancient towers built with large blocks of local stone. Known as nuraghi, they resemble giant beehives, jutting out across the landscape. Little is known about the nuraghi or their Bronze Age architects but almost every Sardinian I met had a theory about their purpose. Some told me that they were forts; others that they were residences, places of exchange, even communication beacons. “The amazing thing is that from every single nuraghe you see another nuraghe,” Carlo Mancosu, a 34-year-old Sardinian, told me. “Now imagine a system of communication with flames or light or mirrors. I think there existed a people in a network.” It was this system, real or imagined, that inspired Mancosu and a group of childhood friends to found Sardinia’s first local currency: Sardex. Arts and humanities graduates with little financial experience, they built it from scratch in their home town of Serramanna as the island reeled from the financial crisis. Their hope was that the project would give them a job in the place where they had grown up. But six years later it has turned into a symbol of local action, spreading to create a new network of thousands of businesses. Together, they have traded nearly €31.3m in Sardex this year. Serramanna sits just within the agricultural region of Medio Campidano, one of the poorest in Italy. When I visited, its piazza was full of old men drinking their coffee under the shade of Canary palms. Only the occasional roar of a jet engine from the nearby Nato base broke the silence. I met four of the currency’s five founders in their office, an old farmhouse in the town. On the wall was a sign in Sardinian and Italian: “Don’t complain.” Giuseppe Littera, another founder, told me that it was intended for his grandmother, who owns the farmhouse. “I love my grandmother [but] she’s still complaining about the Nato base because they took 10 plants from the best olive field their family had.” Now in their early to mid-thirties, the founders all grew up together in Serramanna. “I have traced my ancestry back 500 years,” Giuseppe told me proudly. “They didn’t have earlier records.” They seemed a remarkably disparate group, fiercely debating local politics and the financial crisis. Giuseppe speaks rapidly, moving between Italian and English. Gabriele, his younger brother, is more restrained, carefully balancing his words. Then there’s Mancosu, the most confident of the four. And Piero Sanna, a pragmatic amateur gold trader, whose financial experience initially set him apart from the others. Life in their home town can seem idyllic, with its old church, public spaces and faded murals. But the four presented a different image. “Youth unemployment is at 50 per cent,” Giuseppe said. “The factories are in a state of crisis. Anyone with minimal linguistic abilities escapes to London or Berlin.” One of the stone towers, or ‘nuraghi’, found across the island In the 1960s, planners in Rome decided that the future of Sardinia — an island of miners, shepherds and farmers — lay in industrial production. Countless petrochemical plants, factories and refineries were built as part of the state-led Piano di rinascita (Plan for Rebirth). When I asked Sardex’s founders about the town’s problems, they would often repeat the phrase with a tinge of sarcasm. “Bring hell to paradise,” Mancosu said, “and they call it plan for rebirth.” The island’s nascent petrochemical industry, knocked off course by the 1973 Opec price rise, proved unable to compete in the international market. As the plants declined, thousands were laid off. “We had to face, year by year, an emergency in these industries,” said Stefano Usai, an economist at Crenos, a Sardinian research institute. “It is a heavy inheritance.” Then, in 2008, another wave hit the island: the financial crisis. “Here, 2,000 miles away [from Lehman Brothers], banks stopped lending anything really,” Giuseppe told me. “People stopped going to ask for a loan.” Unable to secure credit, companies started to fold, swelling the ranks of the jobless. “In Serramanna we have a suicide problem.” A Sardex agent At the heart of the financial crisis, explained Giuseppe, was a contradiction: its causes remained distant but its effects were local. “What does the economic system of Sardinia have to do with the mismanagement of Wall Street or London?” he said. The island’s companies still had the potential to produce goods and services; stock was sitting in warehouses and people were able to work. If this was a financial crisis, he began to think, then perhaps there was a financial solution. “There was no other option,” he said, “but to let companies create their own money.” For at least 150 years, business people, utopians, social reformers and eccentrics have tried to introduce local currencies, often in response to money scarcity. Their creations have taken an array of different forms, such as credit systems, time banks or paper money, and ranged from the ingenious to the absurd. Many have been shortlived — but others have outlasted the conditions that brought them into existence. Among the most successful is the Swiss WIR, which first appeared during the Great Depression. In 1934, a network of Swiss businesses decided to build a system of mutual credit allowing them to trade without relying wholly on the Swiss franc. The currency proved remarkably resilient, especially during periods of economic downturn. Although it has changed significantly since its inception, the WIR is still going strong and has about 45,000 members. The office, a converted farmhouse “For his different purposes,” wrote the British economist EF Schumacher, “man needs many different structures, both small ones and large ones, some exclusive and some comprehensive.” For some, local currencies are a financial response to this human need and one that has a strong precedent through history. “The permanent feature of monetary systems in Europe throughout the period from Charlemagne to Napoleon — for a good millennium — [is] a distinction between different moneys for different purposes,” says Luca Fantacci, an economist and historian at Bocconi University in Milan. Sardex began as a small, unlikely idea while Giuseppe was a student in Leeds. In 2006 he read about WIR, the Swiss complementary currency, and became obsessed by the possibility of bringing something similar to Serramanna. “When I went to England and I was still studying, I was kind of trying very hard to find meaning in life. And when I discovered the WIR thing — that was like, OK, it’s a battle worth fighting. The other option is: let’s wait for systemic worldwide change.” He discussed the idea over Skype with Mancosu, Gabriele Littera, Sanna and Franco Contu, another founding member and friend, and they began designing a new local electronic currency whose name, Sardex, left no mystery as to its origins. And so the group of arts students planned a new currency for their island. It seemed absurd: they had little financial or IT experience, no MBAs and no investor, only the outline of an idea. “We said: ‘We are here, the companies are here. [We can do this] without inconveniencing Brussels, Rome or New York,’” Giuseppe told me. To build Sardex, they turned to financial history, drawing on studies of ancient credit systems, the Swiss WIR and John Maynard Keynes’s proposal for an International Clearing Union at Bretton Woods, a version of which was implemented as the European Payments Union (1950-58). There was logic in this approach; for if the financial crisis proved anything, it was that the history of finance is not linear. “There’s no reason to think that financial markets are more progressive than the financial institutions of the Renaissance,” says Massimo Amato, an economist and historian at Bocconi. “Common sense is never outdated.” The Mulargia Lake in southern Sardinia While Sardex’s founders borrowed from history, they were not beholden to tradition. In a recent paper, Paolo Dini of the London School of Economics writes that, “Sardex has institutional characteristics that make it almost unique among the thousands of examples of CCs [complementary currencies] that have existed throughout human history and that still exist in almost every country in the world.” To understand how Sardex works, you have to abandon much of what you may think you know about money. There is no bank that prints Sardex notes; no algorithm that generates Sardex digital coins. Instead, it functions as a system of mutual credit: each firm begins at zero, earning the digital currency — equivalent to but non-exchangeable with the euro — as it offers goods or services to others in the network. Companies may go into debt but only up to a certain limit, determined by what they can offer the other participating firms. Crucially, there is no interest on Sardex; it functions purely as a means of exchange. “[In the circuit] you have a debtor who does not see their debt increase but finds creditors who want to spend,” Gabriele told me. “This should be a natural part of the market.” When Sardex was first explained to me, I found it easiest to think of it as a simple portrait of human relationships. “Money becomes information,” said Mancosu. “But, above all, money [here] is a system of rights and duties. From the moment that I take from a community — as is the case in Sardex — I am in debt towards that community; when I settle that debt with the community, I have given what I have received. It’s a beautiful thing.” The founders, from left: Gabriele Littera, Piero Sanna, Carlo Mancuso, Giuseppe Littera and Franco Contu The root of the word finance is the Latin finis, “end”. For Amato and Fantacci, the two Italian economic historians, Sardex’s simplicity reflects finance’s etymology and its true purpose: it allows a creditor and debtor to come together, make a payment and part ways, ending their relationship. Nothing could be further from the unsustainable repackaged debt, the system of delayed payments, which resulted in the collapse of the banking system in 2008. “[Sardex] is money that serves an end,” Giuseppe told me. “And once that end has been reached — it has done its work.” At the heart of Sardex are its administrators. Using a centralised system, they carefully track member firms’ transactions, occasionally nudging the network to ensure its stability. Did they not, I wondered, resemble those central bankers from whom they had sought to distance themselves? “Sardex is voluntary,” Giuseppe replied. “We have no guns and we have no power.” It proved easier to design Sardex’s system than persuade firms to adopt it. After registering the company in Serramanna in July 2009, the founders began to approach local businesses with their idea. As a group, they must have presented a curious sight: not one typically associated with financial professionals. Hundreds of firms in Sardinia rejected their proposals; after all, they needed euros to pay suppliers, not an invented currency overseen by a group of idealists. “It was a war,” recalled Mancosu. “They looked at us if we were from outer space.” Then, at the beginning of 2010, the founders had a breakthrough: a local businessman, believing he was joining an established network, signed up. “We explained it to him,” recalled Mancosu. “And, for the first time, he said: ‘Great. That’s fantastic. Who else is in?’ ‘Just you,’ we said. ‘But we will grow.’ ” Sardex: how does it work? ● Sardex is an electronic system of mutual credit for Sardinian companies. Lawyers, accountants, media companies, shops, hotels and utility companies all use it. ● To be eligible, a firm must have spare goods or services to offer to participating firms and be willing to make purchases within the network using Sardex. ● All firms begin with zero Sardex, earning the electronic currency as they transact with other members. ● Firms can go into Sardex debt but only up to a limit set by the administrators. No interest is charged on balances. ● Transactions of less than €1,000 must be carried out in Sardex. Larger transactions can use Sardex with euros. ● All transactions are tracked via a centralised system in Serramanna. VAT on transactions is paid in euros. ● Members are charged an annual fee according to size, ranging from €200 to €3,000. And slowly Sardex did. High-street shops, hotels, media firms, accountants, dentists and restaurants all began to enter the network. By accepting payment in the currency, companies found that they could dispose of unused stock; cash-strapped firms could buy goods and services that they couldn’t otherwise afford. Lacking resources, the founders relied on charm, tenacity and, above all, their connection with the local area to persuade businesses to join. “Human relations have always been at the heart of our project,” Gabriele told me. “It has never been possible to sign up to the circuit via the internet.” By the end of 2010, Sardex had a total of 237 members and a modest transaction volume of just over €300,000. It was still a struggle to survive, they recall. Initially the team relied on their families for support, later charging companies a small membership fee based on their size. And then, in 2011, they had a piece of luck: dPixel, a Milanese venture capital firm, intrigued by their idea, agreed to invest €150,000 in the company. “That was a real lifeline,” Giuseppe said. Fifteen years ago, a retired law academic named Giacinto Auriti introduced his own paper money, the Simec, in Guardiagrele, a town in central Italy about the size of Serramanna. A wealthy man, Auriti paid a local printer to produce the currency, distributing it to locals from his own palazzo in exchange for lire. For Auriti, the Simec was not just a local initiative but a front in his long-running campaign against central banks and their monopoly on money production. “Between me and the central banks there is a mortal struggle,” he told The New York Times in 2001. “There is no middle way.” Serramanna, where youth unemployment is high Unlike Auriti, Sardex’s founders have always viewed their currency as complementary to the financial system; they are not waging war against the Bank of Italy. State-issued money remains central to Sardex: firms in its network may combine euros and Sardex when making payments; taxes on Sardex transactions must be paid in euros; and the value of Sardex itself is tied to the euro. “We developed the network to be politically agnostic,” Giuseppe told me. “We talk to everybody: we don’t give a shit if you are from the left, the right, the north, the south.” Auriti did not win his struggle against the Bank of Italy. In 2000 the Italian financial police, the Guardia di Finanza, shut down his experiment. But Sardex continues to grow. Today around 2,900 businesses are using it, including some of Sardinia’s most established organisations: Tiscali, the telecommunications company, and L’Unione Sarda, one of the island’s main newspapers. Stripped of money’s function as a store of wealth, Sardex has circulated quickly; according to the founders’ figures, it has facilitated more than €30m of transactions this year and about €84m since it started. Timeline April 2010: first Sardex transaction Idea inspired by network of nuraghi December 2010: 237 company members 2011: venture capital firm dPixel agrees investment October 2012: €5m credit transactions €31m traded in Sardex this year €84m credit transactions facilitated since 2010 Trials under way throughout Italy “In our circuit, one credit circulates 12 times in a year,” Gabriele said. “No one keeps their [Sardex] credits stuck in their wallet.” The prize for Sardex is now Sardinia’s biggest employer: the state. The team is currently proposing a scheme whereby the island’s regional government could join the network, disposing of its spare capacity, such as bus tickets or leases on property. The deputy governor of Sardinia, Raffaele Paci, is an economist who seems to represent the opposite of these young arts graduates who were so distrustful of mainstream economic thinking. “If we live in an ideal world then we do not need Sardex,” he told me. But he recognised that in this imperfect world the currency had a role to play. “In general, it’s a good experience that is helping a lot.” Some six years after it started, Sardex still faces challenges. In an imperfect market, the network must be pushed and pulled to maintain its stability, placing great responsibility and influence in the hands of its administrators. Then there’s the question of cheating. A system that relies on trust, Sardex allows companies to go into unsecured debt, exposing the network to the risk that a member may rack up a negative balance and walk away. In practice it’s happened a few times, said Giuseppe, and the team now has several claims lodged in Italy’s notoriously slow court system. “It is our last-resort scenario,” he told me. After meeting Sardex’s team, I took a walk around Serramanna to speak with local businesses. The owner of a local store showed me her online Sardex account, indicating her balance and all the firms with whom she could potentially transact. She had sold lingerie to companies in the network, earning Sardex, which she then used to pay her accountant. “It’s ingenious,” she said. “It makes the money circulate here [and] doesn’t allow it to leave the island. It creates a connection.” The model has already spread in Italy and there are reportedly trials under way to create local currencies in Veneto, Piedmont, Emilia Romagna, Marche, Lazio and Sicily. Last year Giuseppe travelled to Greece to share his knowledge with local currency organisers. Yet his advice to them was less about financial models, credit systems and software than relationships and trust. “Focus on the impact you can have, work every day . . . and try to build communities where there are none,” he told them. “[In Sardinia] the social fabric was destroyed. And we started knitting.” Edward Posnett is working on ‘Harvest’, a book about commodities, trade and the natural world, to be published by Bodley Head/Viking Penguin, 2017 Photographs: Alessandro Toscano Source: Dini, P, Van Der Graaf, S and Passani, A (2015). D2.3.d1: Socio-economic Framework for Bold Stakeholders, openlaws.eu deliverable, European Commission